Recently we have been taught the imaginary assembly language used by AQA as part of A level computer science in school. I found these lessons very interesting, and I wanted to try using a real assembly language.

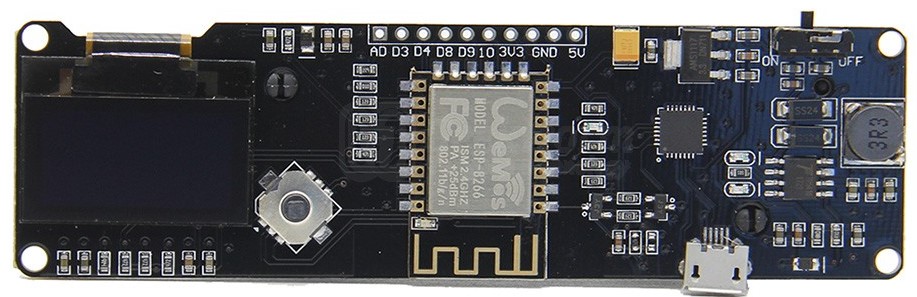

I decided to try the AVR assembly language used by Atmel chips (such as those found in Arduinos) because it is much simpler than, for example, the x86 language used by Intel and AMD processors. The chips are 8-bit microcontrollers, meaning that there aren’t a massive number of instructions. (an interesting fact I learned recently is that the modern manual for the Intel x86 language has more pages than the 6502 processor found in the Commodore 64, BBC Micro, NES, and Apple II had transistors!)

The programs are all in a GitHub repository here.

First program – serial output

The first program I created just outputs a string via the serial connection to the PC over and over again. I relied strongly on this GitHub repository to figure out how to use the serial interface.

Second program – Fibonacci

Now that I had the serial output working, I decided to try and make a program to output the Fibonacci sequence. I used 16 bits to represent the terms, a combination of two 8 bit registers.

Also, I output the terms in hexadecimal because it’s much easier to convert an integer to a hexadecimal string than to a denary string, since each character is exactly four bits. I can perform a bitwise AND with 0b00001111 to get the lower nibble and 0b11110000 to get the upper nibble. For the upper nibble I have to do a swap instruction to get the top four bits to the lower nibble (originally I did four right shifts before I discovered the swap instruction). Finally I just add 48, the ASCII character code of 0, and voila, hexadecimal.

Here is the output of the program. As you can see, it only gets to 0xB520 because the next number needs more than 16 bits and it is set to halt when it overflows.

Third program – string reverser

For the third program I wanted to use the stack beyond just calling subroutines.

I created a program that takes an input string over serial, pushes each character to the stack one by one until it encounters a newline, then pops and prints each character one by one.

Here it is in action. I made it print ‘>’ as a prompt to try and make it clear which lines are user input and which lines are output.

Fourth program – multiplier

For the next program I wanted to try accepting user input and giving output in denary instead of hexadecimal. I created a program that takes two positive integers separated by an asterisk (and optional spaces which are ignored) and outputs the result of multiplying them together.

The two inputs are stored using 8 bits each, so the maximum is 255, while the result is stored using 16 bits, allowing numbers up to 65535 to be calculated.

Converting the ASCII user input into an integer wasn’t too difficult – as the characters are entered, they are pushed to the stack (except space). When an asterisk (for the first number) or a newline (for the second number) is encountered, a subroutine is called to process the number. For each character from right to left (because they’re popped from the stack in reverse), it subtracts 48 (the ASCII code of the character zero), multiplies by a power of 10, and adds the result to the sum. The digit multiplier is multiplied by 10 on each number (1, 10, 100). For example, the string ‘123’ would be calculated using (3 * 1) + (2 * 10) + (1 * 100).

By far the hardest part was converting an integer result back to a denary string. I divided the integer by successive powers of 10 (10000, 1000, 100, 10, 1), each time using the remainder of the previous calculation. This gave me the value of each digit, which I could then add 48 to to get the correct ASCII characters which were then printed. The issue was that Atmel AVR chips don’t have a divide instruction, so I had to implement division in software. However, to implement division I had to multiply 16 bit numbers, which added more complexity because the chips can only multiply 8 bit numbers. However, I got it working in the end.

As you can see in the image below, if either of the inputs are above 255 they overflow.

I’ve enjoyed figuring out how to do these basic things with assembly language and it’s given me an insight into how computers work at a low level. It’s also made me appreciate how useful high level languages are!