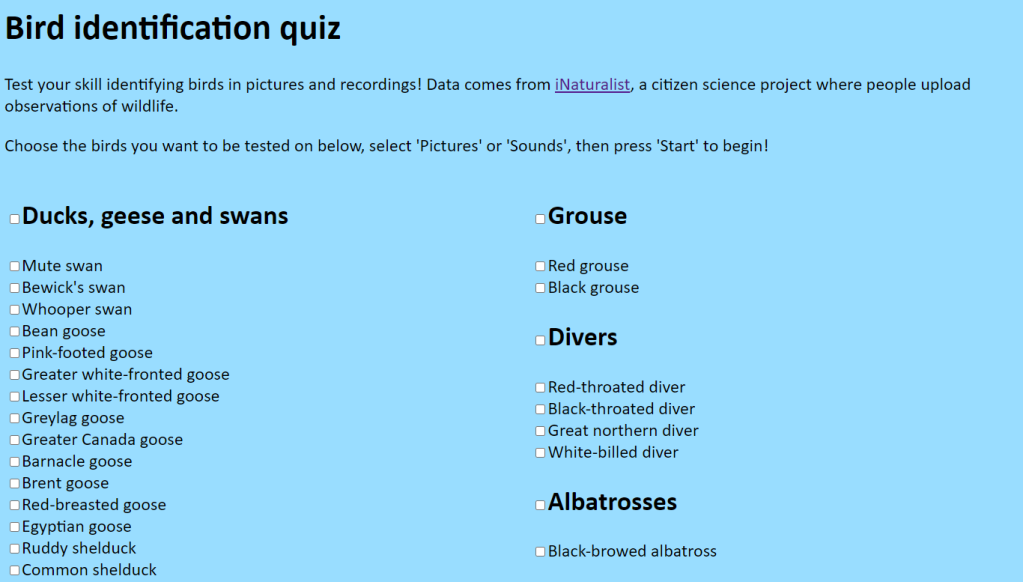

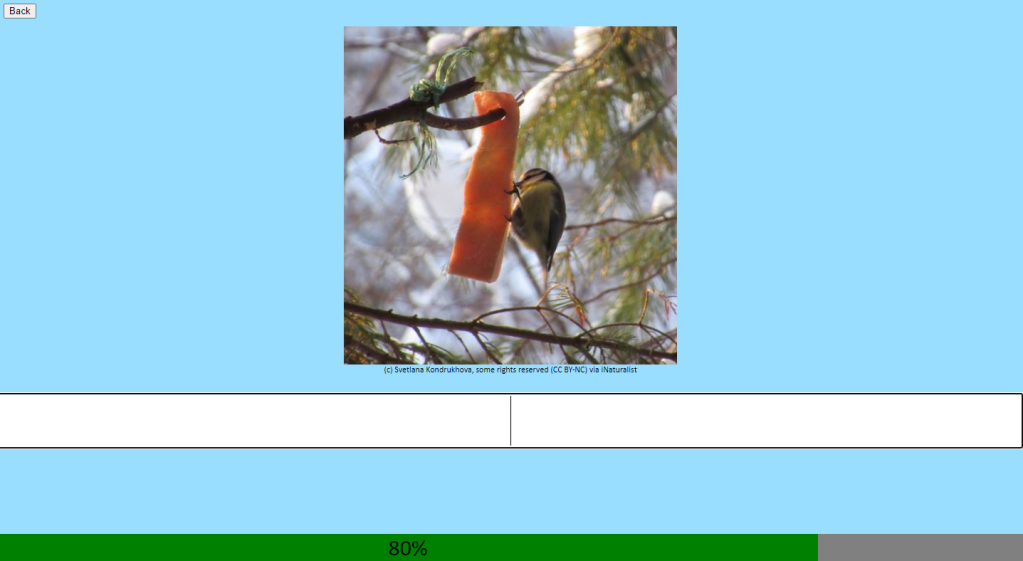

Over the summer holiday I’ve been working on a project to try and simulate some of the processes that occur in the cardiovascular system. I wanted to do this because I enjoyed our first year physiology course and wanted to put some of the concepts we’ve learnt into action in a simulator, and also because I wanted an opportunity to gain more experience with TypeScript.

The program produces a rough simulation of the velocity of blood flow through the aortic valve and the resulting pressure in the aorta over time. The user can give the patient diseases that modify the properties of the model to see how the flow and pressure is affected. However, the model doesn’t simulate any time-dependent processes such as autotransfusion, only the initial steady state. It also doesn’t model any blood chemistry, and it only encompasses the systemic side of the circulation (the aorta to the right atrium). I chose to use human data because this is the species for which I could find the most information.

You can try it out in the browser here, and the source code is on GitHub here.

The Windkessel model

The core of the simulator is the Windkessel model. This models the circulation as an electric circuit, where current represents flow and voltage represents pressure. I used the three-element Windkessel, so called because it has three electronic components: a resistor to represent the proximal resistance of the aorta, a capacitor to represent the compliance of the proximal arteries, and a second resistor to represent the peripheral resistance of the rest of the systemic circulation. These three components are connected as shown below.

Based upon Ohm’s law and the behaviour of capacitors (with charge representing the volume in the artery) it is possible to derive a differential equation linking the time derivative of voltage (pressure) to the current (flow) entering the circuit, or it is also possible by considering Darcy’s law of flow and the definition of compliance, which I have done below.

On the line marked [*] it is assumed that the venous side of the circulation is at a pressure of zero, which is unlikely to be true. However, the pressure should generally be sufficiently low for this assumption to be valid.

The differential equation derived can then be combined with a waveform describing the flow out of the aortic valve over time, values for Ra, Rp and C and boundary conditions (initial values for t and p) and solved numerically to generate a waveform of aortic pressure. I solve it over a time period of ten seconds then take the final beat of data, as I found that by this point it reliably reaches a steady state.

For the flow waveform I initially used the function below which I found here, which uses a single sine wave to model both the systolic flow and the dicrotic notch.

I found that the discontinuities where the value changes suddenly created strange jumps in the pressure waveform that didn’t match the experimental data I could find very well. I created the below similar but continuous waveform using two sine waves that seems to better match experimental data.

The details of the waveform such as the length of systole and of the dicrotic notch are controlled by parameters.

For Ra, Rp and C I used base values derived from Wikipedia.

Implementation

The behaviour of the model is controlled by a collection of parameters, encompassing both the Windkessel values Rp, Ra and C and also values modifying the flow waveform such as the length of systole, the maximum achievable stroke volume, heart rate and so on. They are stored as Parameter objects in a CirculatoryParameters object and passed on to Heart, which creates the flow waveform, and Vasculature, which evaluates the resulting pressure waveform.

The values of the parameters are all calculated by starting with a base value and applying factors, of which there are three types: exercise, baroreflex, and disease. The exercise factor represents changes to the parameter due to exercise. For example, the peripheral resistance Rp decreases due to vasodilation of arteries supplying muscles. Meanwhile, the baroreflex factor represents changes initiated by the baroreflex, such as an increase in heart rate when mean arterial pressure drops below 93 mmHg. Finally, disease factors (of which there may be multiple for a single parameter) represent changes due to diseases the user has given the patient, such as a decrease in arterial compliance C due to atherosclerosis. The Parameter class and its child SummarisableParameter are responsible for storing the base value and factors and calculating the resulting value for a single parameter.

The base values and magnitudes of factors affecting the parameters were largely obtained from my course notes and the internet combined with some reasonable-seeming guesses – I believe they are sensible, but of course are unlikely to exactly correspond to any real human patient.

Disease factors are determined by Disease objects, which store the user-set severity of a disease and calculate the resulting disease factors (with the factors increasing/decreasing linearly with severity). Diseases can actually produce ‘additors’ as well as factors, which are values that are added together before being multiplied with the base value. This was necessary to enable changes caused by opposing diseases such as hypovolaemia and hypervolaemia to cancel out. Classes representing specific diseases such as Atherosclerosis and HeartFailure inherit from the base Disease class. An instance of every Disease subclass is stored within the static DiseaseStore class, which provides methods for PatientGui to retrieve string names of diseases, and to set their severities based upon these names.

The other type of value being passed around by the model are outputs. These are represented by the Output class and stored in the CirculatoryOutputs class. These values are calculated based upon the flow and pressure waveforms generated. For example cardiac output, stroke volume, mean arterial pressure and pulse pressure are outputs.

Heart, Vasculature, CirculatoryParameters and CirculatoryOutputs instances are all aggregated by a CirculatorySystem class, which passes the necessary data between them. CirculatorySystem also carries out the baroreflex by incrementally adjusting baroreflex factors until the mean blood pressure is equal to the baroreflex set point parameter, if this is possible. An instance of CirculatorySystem is stored in Patient, along with an array of references to active Disease objects.

Parameters and outputs are communicated to the PatientGui object responsible for displaying them via ParameterSummary and OutputSummary objects that contain data such as the value, units and descriptions, and for parameters the base value, factors affecting them and explanations behind those factors. Communicating through these objects avoids creating dependencies between the GUI code and simulation code, and also simplifies communication since everything about a certain parameter/output is contained within one object. When the user wishes to set a value PatientGui communicates with the rest of the system through callback functions, again to avoid dependencies.

The static ClinicalSigns class examines the values of parameters and outputs to determine some symptoms the patient is likely to be experiencing, as an array of strings. For example, if mean arterial pressure cannot be maintained above 90 mmHg at high exercise intensity the patient is likely to have exercise intolerance, or if cardiac output at rest is below 4 L the patient is likely to have some cyanosis.

A class diagram of the program can be seen below.

Simulating heart failure

Normally, cardiac output is limited by the mean systemic filling pressure – this determines how much blood can be pumped out of the venous system before the pressure drops below zero and vessels start to collapse. The heart will always pump all venous return, with the Starling mechanism ensuring this by increasing stroke volume and contractility as preload (right atrial pressure) increases.

However, in heart failure cardiac output is instead limited by the heart itself. This is because the Starling curve is depressed, with a lower peak (as shown below). There are two types of heart failure that both cause this change. In heart failure with reduced ejection fraction the fraction of blood pumped out of the ventricle with each beat is decreased. This is due to dysfunction during systole leading to reduced contractility (force) and thus decreased emptying. It can be seen in diseases such as dilated cardiomyopathy and due to infarction caused by coronary artery disease.

The other type is heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, where the fraction of ventricular volume pumped out with each beat is unchanged. Here the issue is instead diastolic disfunction, which causes impaired filling of the heart such that there is a smaller volume of blood in the ventricle at the start of systole. This type of heart failure can be seen in diseases such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, mitral stenosis or atrial fibrillation.

What all these diseases have in common is that they all result in a decreased maximum stroke volume – this is thus how the model simulates heart failure. Normally the model determines stroke volume by calculating the total venous return (using VR = (MSFP - RAP)/RVR where MSFP is mean systemic filling pressure, RAP is right atrial pressure and RVR is resistance to venous return, and RAP is assumed to be approximately zero) and dividing this by the heart rate – this simulates the Starling model adjusting stroke volume to match venous return. However, when heart failure is active, the stroke volume is capped at a maximum value that decreases with disease severity. To ensure Darcy’s Law is still obeyed, a new elevated right atrial pressure is calculated so that the new cardiac output matches venous return.

This shows the output of the model when fairly severe heart failure is applied. The stored waveforms for a healthy patient are shown in red behind the green heart failure waveforms. A fall in mean arterial pressure at high exercise intensity results in exercise intolerance. The model also predicts an increase in heart rate (tachycardia) as the baroreflex attempts to maintain mean arterial pressure despite the lower stroke volume. Interestingly, apparently this is found in some but not all patients. I wonder if perhaps the baroreceptors in some patients adjust to a lower set point over time, but I was unable to find an explanation online.

I’ve enjoyed working on this project and it’s helped improve by understanding of cardiovascular physiology. In future I’d like to add more diseases and clinical signs, and also let the user prescribe medications such as beta blockers and observe their effects.